Livestock Wx

Derecho: What are They and Can we Forecast Them

- Becky Bolinger

- August 21, 2020

- 4:26 pm

It’s been a week and a half since a derecho tore across Iowa, but the evidence of this very powerful storm remains – widespread devastation to corn crops, damage to buildings, thousands still without power, many homeless. This may be the first time you’ve heard the term derecho or witnessed the power of one, and you may be thinking 2020 is of course just bringing us new meteorological hazards. But the term was first coined in the late 19th century, and they’ve been part of meteorologists’ vocabulary since the 1980s. So, what are they? Where and when do they happen? Can you prepare for the next one?

Derechos are “swaths of straight-line wind damage”

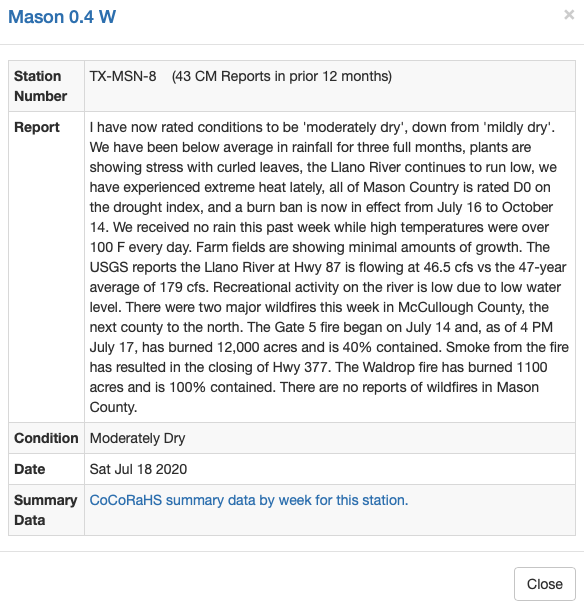

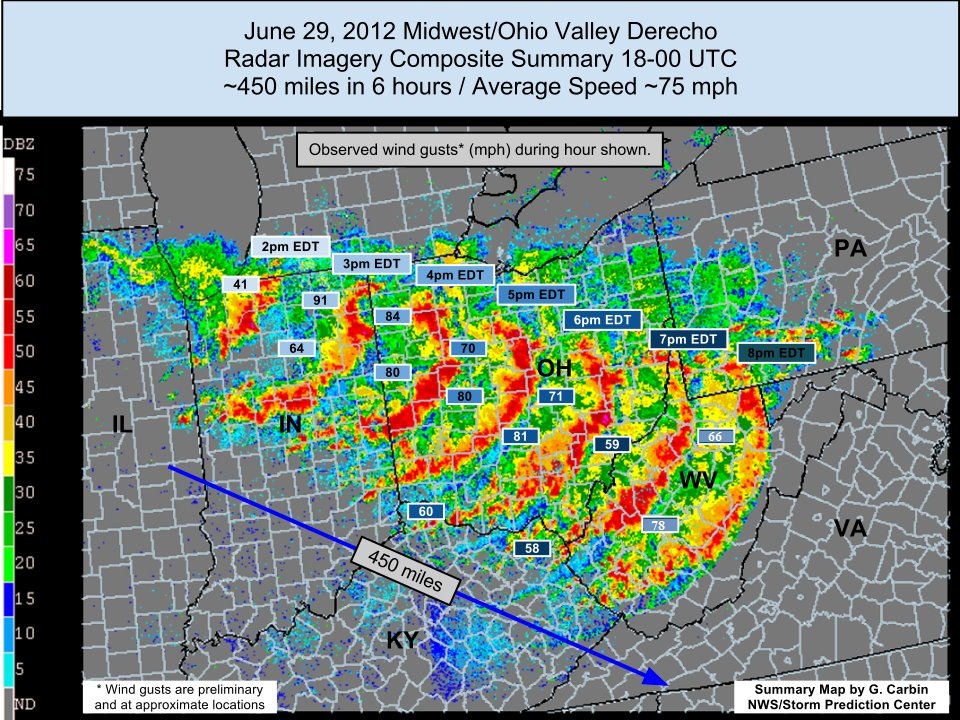

NOAA’s Storm Prediction Center has defined specific criteria that must be met for an event to be considered a derecho. First, a concentrated area of convectively induced (i.e. thunderstorm) wind gusts greater than 26 m/s (58 mph) would be observed over a major axis length of 400 km (almost 250 miles). The image below, from the National Weather Service, shows an example of a derecho in 2012. The radar imagery helps meteorologists assess the scope and structure of the event, and the numbers are the observed wind gusts during the event.

The potential winds and subsequent damage from a derecho can be equivalent to an EF-0 to EF-2 tornado (an EF-2 can have winds from 111-135 mph with considerable damage). But derechos are distinctly different from tornadoes. First they are much more widespread. And the winds associated with them aren’t necessarily rotating, which is why you may hear the term “straight-line winds.” These wind speeds are partly due to how fast the storm is traveling.

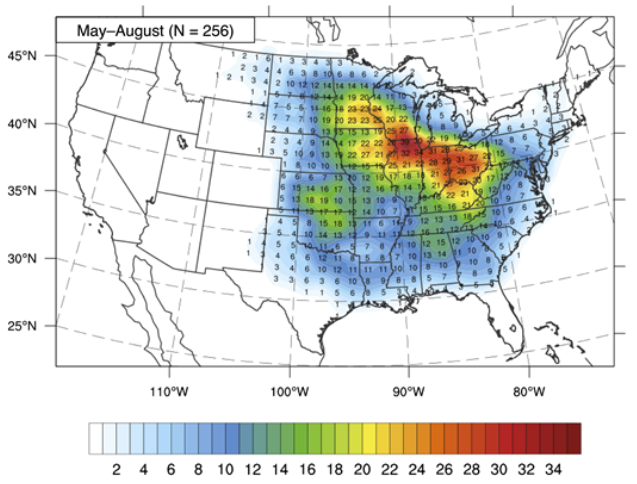

In 1998, Bentley and Mote did an analysis on the climatology of derechos. While different types of derechos can happen any time of year, they are most common in May, June, and July. They found that derechos that originate in the northern Great Plains and travel in a southeastward pattern tend to last for around 10 hours! The graphic below, from Guastini and Bosart (2016), shows where derechos are most common in the United States.

Can meteorologists predict derechos?

With each passing year, numerical weather prediction is getting better and better. But predicting the potential formation of a derecho is particularly challenging. The Storm Prediction Center and National Weather Service offices are very good at identifying areas where severe weather is likely to occur a day or two in advance. Like it’s hard to know which thunderstorm will produce a tornado, it’s difficult to know which line of storms may organize into a larger scale derecho. Once a derecho has formed, there are new challenges with forecasting its speed, strength and direction (based on the complexities of the storm itself, but also of the surrounding environment). But it has been possible to warn people several hours ahead of an advancing derecho so that precautions can be taken.

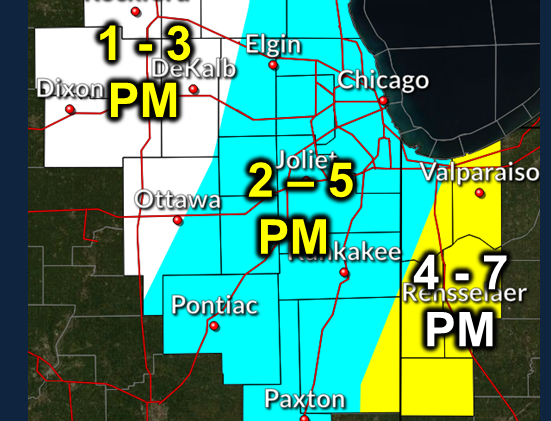

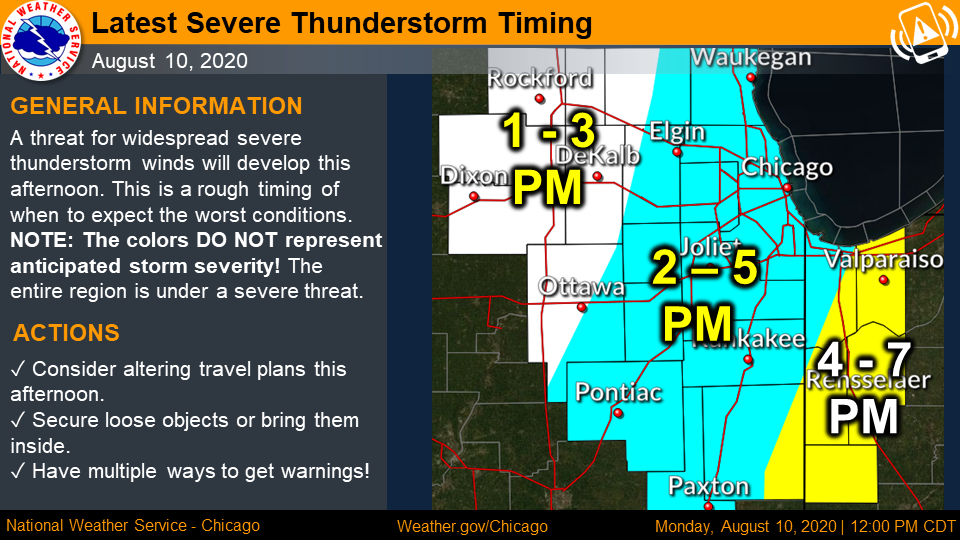

Take the August 10th derecho for example. On August 9, the SPC did not see any indication of potential for derecho development, though they did note there was marginal risk for severe thunderstorm activity associated with a cold front moving across the region. By the morning of the 10th, forecasters were aware of the developing situation and had placed eastern Iowa and northern Illinois in an area of enhanced risk for severe thunderstorms. By noon, the Chicago National Weather Service office had released this forecast of the arrival of the derecho storm, well in advance of the 2pm-5pm arrival. See graphic below.

This is a good reminder to always be prepared for severe weather in the summer months. Check your local National Weather Service office’s website daily; keep up-to-date on the Storm Prediction Center’s maps of where the risk for severe weather is expected over the next couple of days; and get a good radar app on your phone to keep your eye on any storms headed your way (my personal favorite is RadarScope).

The derechos of 2020

It’s been an active year for derechos (because of course, 2020). According to Wikipedia, the following derechos have occurred this year:

April 28-29, 2020 – the Southern Plains-Ozarks Derecho

May 3, 2020 – the Kansas-Tennessee Derecho

June 3, 2020 – the Pennsylvania New Jersey Derecho – This event left over half a million people without power and took the lives of 4 people, three of them from falling trees.

June 6-7, 2020 – Rocky Mountains Northern Plains Derecho – One of the most surprising elements of this derecho was that it crossed the Rocky Mountains from Utah and through Colorado, with a 110 mph wind gust reported at the Winter Park Ski Resort. I personally remember this one as I headed to the grocery store and warned my husband and daughter to bike back to the house before the storm hit. They barely made it in time before the storm arrived, whipping through.

June 10, 2020 – Great Lakes Derecho – The below image (wind_reports.png) shows the high volume of wind reports during the event that left 700,000 people without power. It also produced 7 tornadoes across Ontario, Canada.

July 7, 2020 – Northern Plains Derecho

July 17, 2020 – North Dakota-Minnesota Derecho

August 10, 2020 – August 2020 Midwest Derecho – A complete overview of the August 10th storm can be found at the following links: NWS Des Moines, NWS Quad Cities, and NWS Chicago. The National Weather Service has been surveying the damage. They’ve shared the below picture (wind_estimate.png) with wind estimates. Based on wind damages, they’ve estimated peak wind gusts at 140mph in Linn County, Iowa. Damage has been widespread and devastating, including destruction of 250 homes and 700 sustaining significant damage, and sweeping losses of corn crops.