Calving in an El Niño Winter

When a shivering cold and wet, wide-eyed baby calf was born on an unusually frigid El Nino Kansas evening in late February 2019, the resulting turn of events were proof that miracles happen but can’t be taken for granted. Right on the heels of this calf (named ‘Laurie-Bell’) coming into this world, El Niño’s peak onslaught arrived; heaving a relentless stream of bone-chilling, frosty nights and days from late February into March.

For heifers and even seasoned cows, delivering their newborns this season became especially daunting when compounded by an unsympathetic Arctic airmass that thrust single digit temperatures and a piercing north wind through two-foot snow drifts covering many Midwestern farms.

“This winter has been the result of a triad of weather features: an emerging El Niño, a weak Arctic Oscillation, and an active Madden Julian (pattern,)” explained Mary Knapp; Assistant State Climatologist, located at Kansas State University in Manhattan, Kansas.

“The emerging El Niño favors wetter than normal conditions. The weak Arctic Oscillation favors repeated polar vortex – with incursion of cold Arctic air into the Plains. The active Madden-Julian results in frequent storms making their way across the U.S. As these continue, stress on livestock, and those caring for them also continues,” added Knapp.

In the case of the chilled calf ‘Laurie-Bell’ – she was quickly dried and warmed with an oversize bath towel and a home-quality blow dryer. Warming the calf’s body first was vital, followed by extensively warming its wet fur clad to its’ hooves.

While sadly at first, this calf’s new momma, didn’t immediately ‘claim’ her newborn through the typical, critical initial physical and emotional attachment, the baby calf in this case was able to get a jump-start in life when fourth-generation farmer/rancher Larry Hadachek; Cuba, Kansas quickly warmed up the calf, and fed it – a colostrum ‘protein shake’ using an esophageal tube, to be sure nutrients made it past a loud, unyielding mouth and down the calf’s left side, into its stomach.

“Sometimes she doesn’t realize that’s her calf, if humans are helping and using a puller. She’s having to strain to get the calf out, and what she may be thinking – is that she’s in pain, and she may be blaming the calf for the pain. That’s why you have to shut them up; momma and newborn together alone. You don’t want to turn them out on their own, because she could just walk off, if they haven’t bonded,” said Hadachek.

2018-2019 Winter

The National Weather Service notes – high winds, freezing rain or sleet, heavy snowfall, and dangerously cold temperatures are the main hazards associated with winter storms, as well as slick roads from ice or snow buildup which can result in vehicle accidents. The severely cold temperatures and wind chills during and after a winter storm can lead to hypothermia and kill anyone caught outside for too long. As ranchers know all too well, this potent El Niño season has hit precariously hard for humans and animals. Farmer/rancher Claygatt Shulda, of Republic County, Kansas, agrees – this El Niño winter ranks as the most difficult calving season he remembers.

“I’ve been doing this for over 45 years, and this is the worst winter so far, I think with the extreme cold, and all the moisture and snow,” said Shulda who has a mostly Red Angus cow-calf herd. Clay’s wife Connie Shulda says it’s been a brutal El Niño winter.

“My husband pretty much sleeps in his recliner in his clothes and his coveralls so he can get up every two hours and check on calves. He’s been doing this non-stop from February 1st through March 8th,” said Connie, who’s also a full-time nurse.

For heifers and even seasoned cows, delivering their newborns this season became especially daunting when compounded by an unsympathetic Arctic airmass that thrust single digit temperatures and a piercing north wind through two-foot snow drifts covering many Midwestern farms.

Keep Those Calves Warm

A Nebraska extension specialist says keeping the calf with its momma, is always the best choice – otherwise, a rancher needs to intervene to be sure the calf warms up and eats.

“It is best if they suck rather than having to be intubated and they won’t suck if they are cold, so warm first,” said Karla Jenkins, Cow Calf, Stocker Management Specialist/University of Nebraska-Lincoln at the Panhandle Research and Extension Center in Scottsbluff, Nebraska. “If a barn is not an option, then getting them dry and warmed up in the house is recommended; probably a warm bath followed by a blow dryer and heat lamps. Once returned to momma, providing a windbreak and bedding is the best you can do if you don’t have a barn,” said Jenkins. Heating mats are also available at farm stores to warm up the calf from bottom side-up. Other choices: hot boxes; a small room or box that has heat or heat lamps. It’s vital to feed colostrum as soon as possible.

“Cold calves can’t absorb colostrum effectively. Provide them some warm fluid (electrolyte) to warm the insides first while using other methods to warm the outside. Then provide colostrum,” recommends Sandy Johnson, Ph.D., Extension Beef Specialist/Northwest Research and Extension Center; Colby, Kansas.

Vital Steps for Newborn Calves in The Unseasonably Cold El Nino Winter

Even as El Niño’s winter stronghold plays tug-of-war with ranchers in this critical calving season, beef specialists in the nation’s heartland are urging cattle producers to take specific critical steps when handling a shivering, cold, wet newborn calf – when its momma doesn’t ‘claim’ it.

If the mother’s there – she will handle it. It also helps to have some ‘calf claim’ to sprinkle on the calf, as it attracts the mother to lick it and help them bond. However, when a rancher needs to intervene in this case, it’s vital to:

1. WARM the Newborn Calf

Immediately warm-up the calf, with a towel and/or blow-dryer, a heating mat, warm room, or even a warm pick-up truck. Also-have colostrum on hand, and immediately mix a package with warm water.

2. The Safe Way to Feed A Newborn Calf

“If you have a calf unable to sit up, you can feed with an esophageal tube down its left side, which should correctly get in to the stomach. If they lay flat, however, there’s a high probability fluid could come up and aspirate into the lungs where you don’t want it to go!” cautioned Dr. Rick Holloway, DVM., Animal Clinic in Belleville, Kansas. “So, after you feed the calf, its strongly recommended you keep them propped up. I would never let a calf lay on its side after I ‘tubed’ them. I always make sure they’re sitting upright for at least a couple of hours,” advised Dr. Holloway. “Otherwise, that liquid goes into the respiratory tract, and they get ‘aspiration pneumonia,’ and… they literally drown.”

Dr. Holloway says if a producer has a calf who can hold its head up and can lay on its sternum (breastbone-at the front center of the chest,) then – “You won’t have problems with ‘aspiration pneumonia.’ But if you have a calf who cannot hold its head up, or on its’ sternum…they need to be propped up,” said Dr. Holloway, adding, “You have to take your precautions.”

The intensely frigid, snow and wind chills can chill the calf; causing a negative start to its young life. “When they’re that cold, everything works at a much slower pace,” noted Dr. Holloway.

Prop them up…and here are a few ways to do that…

3. Ways to Prop-Up the Newborn Calf

“You can use a bale to prop them up, and we’ve even used a foot and a half railroad tie. Also, if they’re not flopping around, putting their legs in the right place can work,” said Dr. Holloway.

Another veterinarian also agrees – properly feeding and warming are paramount. “Whatever it takes to get them warmed up – so they’re not hypothermic. It can be on the floor of a pickup or hot box, whatever to warm them up. Warm the extremities too (legs;) the whole body, and get that colostrum in soon as you can,” said Gregg Hanzlicek, DVM, Ph.D., Veterinarian at Kansas State Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory at Kansas State University; Manhattan, Kansas. “If you’re using the tube, it’s important that they’re standing up between your knees, to prop them up between your feet, just so they’re lying on their sternum. Absolutely do NOT ever give colostrum when they’re lying on their side,” advised Dr. Hanzlicek.

4. How to be sure the esophageal tube is correctly administered

“Look on the calf’s left side of its neck and if you can see, or feel the tube past their jaw you’re doing it correctly. If not, start over,” advised Dr. Hanzlicek.

Otherwise, Dr. Hanzlicek warns, you’ve put it on the OTHER side, and you’ve drowned them. “The tube needs to go into the esophagus and not the trachea. If you can feel the tube slide past your fingers (on that left side) you’re okay.”

Within the first two hours after birth, it’s critical to get the colostrum into the newborn calf because their ability to absorb it, decreases with age.

5. Give the entire two quarts of colostrum and warm it up

“You have to get the whole two quarts in; because it contains the minimum amount of antibodies they need. Also, be sure to warm the colostrum so that you’re also warming up the internal organs,” advised Dr. Hanzlicek, noting, “It’s fine to dry the calf while you’re feeding him/or her. That colostrum needs to be provided, immediately.”

While the bulk of the intense cold is slowly waning and morphing into spring…as Dr. Holloway put it, “Now we’re fighting the mud…”

If the cow won’t/can’t get the calf dry initially, the producer can also warm it on the floor of the pickup, or through other options. If calf is chilled, use a thermometer to monitor calf warming progress,” said Johnson. Heated calf boxes need to be kept clean, as too much moist air in the box can create a new problem; pneumonia. “It’s best if there are bedded areas that calves can access with no cows. If there’s no overhead shelter, bed heavily. If the only semi-dry area for calves to lay down is next to a bale feeder, calves will find it and are at high risk for injury,” cautioned Johnson. That’s because cows gathered there to eat, could step on a little calf.

A veterinarian who oversees a livestock program with the University of Nebraska-Lincoln said this winter ranks high on the list of challenging winters which stressed late gestating cows, as well as calves being born.

“It’s a year where good calf vigor is at a premium, meaning calves that are really strong and can bounce up – have an edge opposed to calves who don’t. We know that cows that are in higher levels of body condition (5 or above) will tend to have calves who get up and nurse faster. We know that calves born without calving difficulty, can get up quicker,” said Dale Grotelueschen, DVM, Director of the Great Plains Veterinary Educational Center, UNL; located at Clay Center, Nebraska.

Grotelueschen says it’s important to just be there and get that calf moved to a warm environment. “You just need to get the core body temperature warmed up and continue to warm them until the extremities (legs) warm up. You can also use a rectal thermometer to monitor how well you’re doing on your warm-ups,” he added, noting this winter has been a grim reminder how important those things are.

Additionally, since any chilled calves are obviously stressed, being chilled can result in lower levels of colostral absorption. “So, even though we give them enough, they may not absorb the colostral protein as well as if they weren’t chilled, so that’s a complication we need to monitor, because we know that calves which have compromised colostral absorption, are at greater risk of scours and pneumonia,” cautioned Grotelueschen.

For heifers and even seasoned cows, delivering their newborns this season became especially daunting when compounded by an unsympathetic Arctic airmass that thrust single digit temperatures and a piercing north wind through two-foot snow drifts covering many Midwestern farms.

Spring Outlook

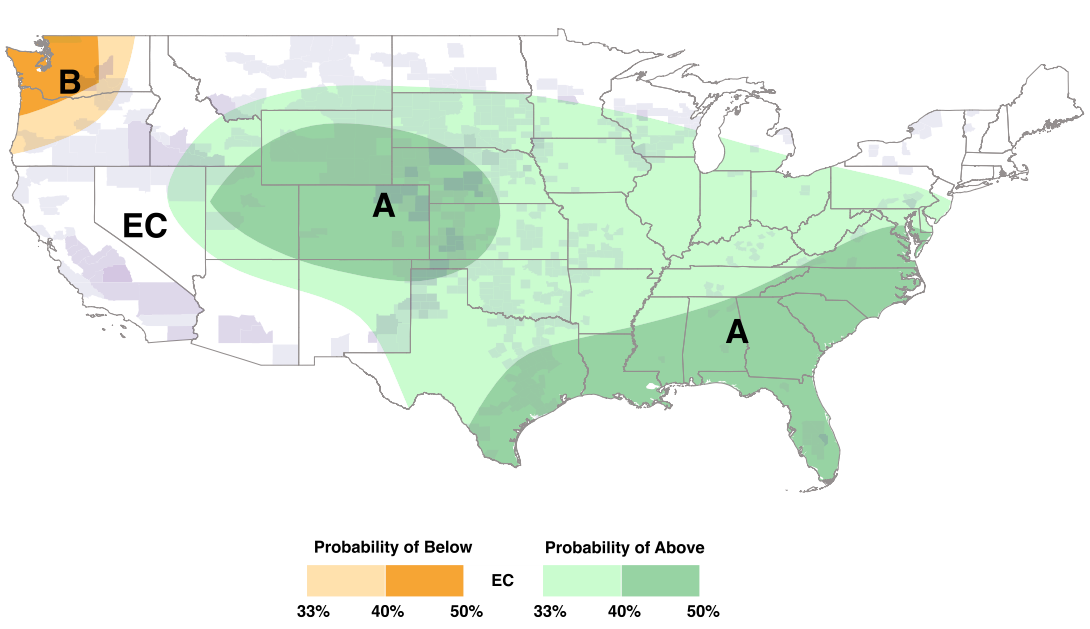

Even with some recent melting, early spring doesn’t guarantee the end of a cold El Niño period. The spring 2019 Outlook from the Climate Prediction Center forecasts above normal precipitation through March for the southern half of the U.S.; east of Nevada. Temperatures in the Plains states and the Rockies have an equal chance of either normal, above or below normal temperatures. Any melting of the record-heavy snow creates a muddy mess for cows giving birth to newborns in the mud and the muck. That’s when additional bedding is recommended.

Another concern, forecasts of moderate to heavy rain in March and possibly April. Near rivers, flooding is another concern.

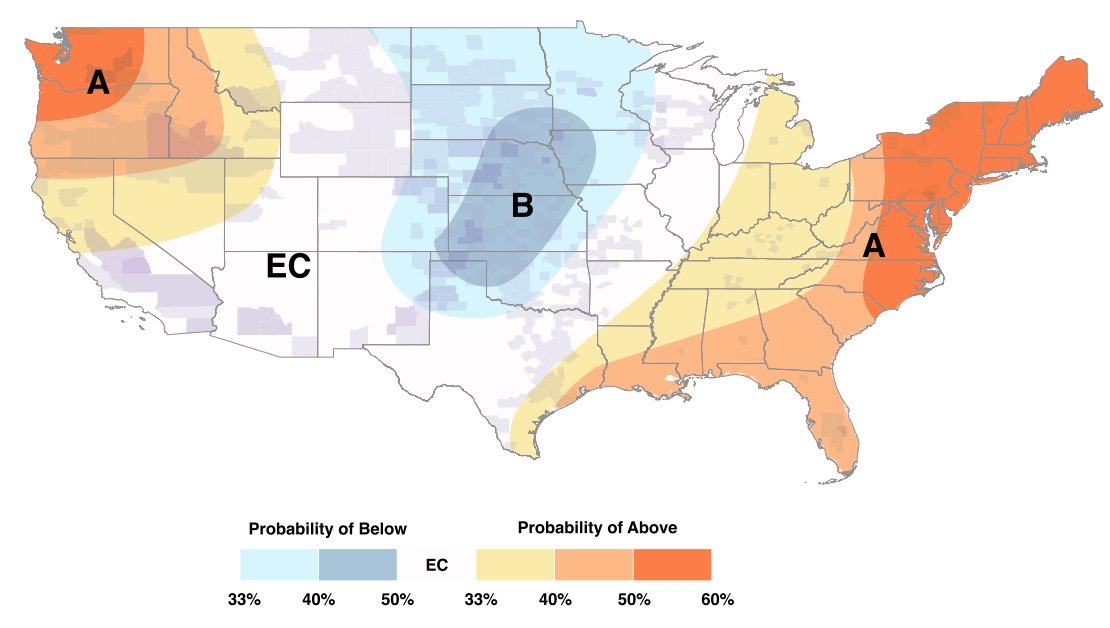

While the CPC April outlook keeps predictions largely cooler and wetter than normal, there is hope.

“For what it’s worth, normal highs in Manhattan, Kansas, for example, at this time are 56F, by the 1st of April that jumps to 62F,” Knapp observed.

Meanwhile, remaining vigilant alongside ‘mother nature’ is paramount. As Clay and other ranchers learned this challenging calving season, “Just stay after it. We just try to keep an eye on it all”.

April-May-June Seasonal Outlook

Temperature Outlook

Precipitation Outlook